I’m just happy hanging out with the fish (as long as they aren’t too big!) But imagine what it must be like to uncover a treasure that’s been hidden on the sea floor for hundreds of years. Imagine discovering the seventh wonder of the world.

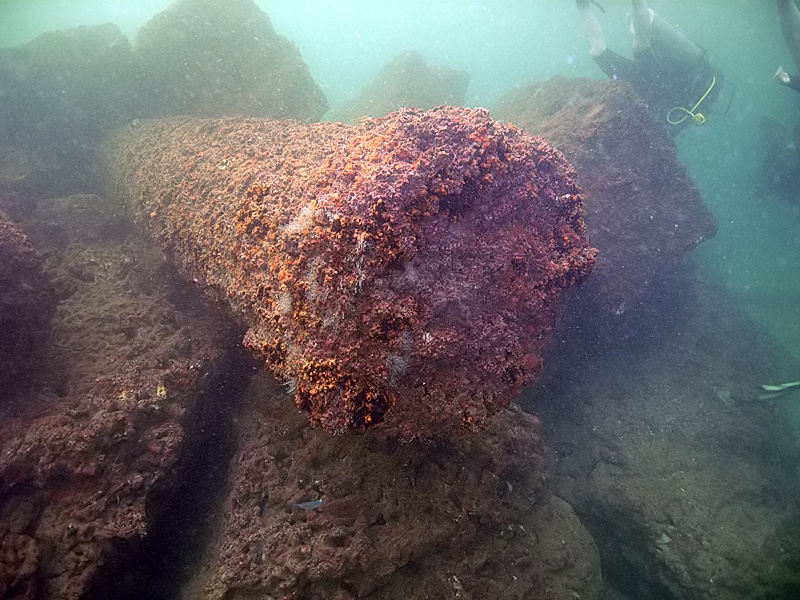

What must it have been like in 1994 when marine archaeologist Jean-Yves Empereur and his team came across a granite block on the sea bed near the harbour entrance of Alexandria in Egypt? On closer inspection, it turned out to be the torso of a massive statue. And nearby lay a giant head with a pharaoh’s crown. A truly majestic discovery. It was the statue of Ptolemy II who ruled Egypt in the third century BC. Experts believed it had once stood at the base of the legendary Pharos lighthouse.

Using underwater technology they began mapping the site and by 1998 they had identified 2500 pieces of stonework – columns, sphinxes, statues, obelisks and immense architectural blocks as big as cars. Given their position, they were beyond dispute from the famous lighthouse.

The first person who drew attention to the site in 1961 was an amateur Alexandrian diver, Kamel Abul Saadat. He persuaded the navy to raise a 25 ton statue of a queen who had the features of the Egyptian goddess, Isis. It was Ptolemy’s wife. After that a blanket of mud covered his finds. But his drawings and notes inspired those who followed.

Isis. She was the goddess associated with magic and love. I liked the idea that she had been lost, found and resurrected. Like the lighthouse guiding sailors into harbour, she seemed a symbol of hope.

Looking back, she must have put some kind of spell on me because when I went diving the first inklings of a story began to bubble up. Swimming across a coral reef, I watched a blue fish skim away out of reach. It glinted like polished metal …

Anyone who has read The Mirror of Pharos can guess what darted through my mind. I hung there in a dream listening to my own breathing. The sea had just delivered a fragment of something special.

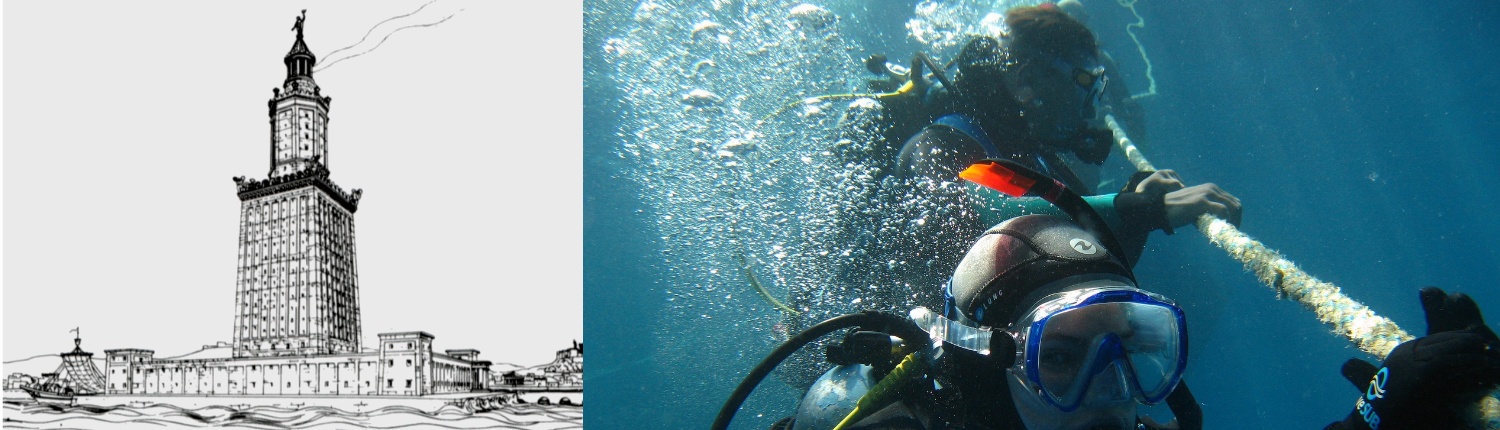

The Pharos lighthouse

The first ever lighthouse was named after the island on which it stood: Pharos. The structure was so famous that ‘pharos’ became the origin of the word ‘lighthouse’ in many languages, including French (phare), Italian and Spanish (faro) and Portuguese (farol).

Building began in 280 BC and the lighthouse stood for more than 1500 years until it was destroyed by earthquakes in the 14th century. The remaining stone was used to build Quaitbay Fort which stands on the same spot, guarding the harbour to this day.

The lighthouse was constructed in three stages like a giant skyscraper; the lowest section was square with a central core, the next octagonal and the top cylindrical like a mosque. At 135 metres high, it was the tallest building in the world.

The source of its light is much debated. Historians suggest a large curved mirror made of polished metal was positioned at its apex reflecting the sun by day while giant fires burned at night. The beam was so powerful it could be seen up to 30 miles away. Some claimed it could even be focussed on an enemy ship to set it ablaze and attributed the mirror’s design to the legendary mathematician and scientist, Archimedes.

Archimedes’ burning mirrors

Archimedes was born in 287 BC in the Sicilian city of Syracuse. The son of an astronomer, he studied in Alexandria in his youth. He wrote important works about geometry, maths and mechanics and is so revered there’s even a crater on the moon named after him. Here’s a fun animation telling the story of one of his most well-known discoveries. How taking a bath led to Archimedes’ Principle.

He was a very practical man. His genius inventions included the hydraulic screw, a machine for raising water to a higher level. It is still used today for irrigating fields in developing countries.

Whether he had a hand in creating the Pharos mirror is a matter of debate. However, he did develop many ‘engines of war’ to defend Syracuse from the Romans. They included his famous burning mirrors. According to historical accounts, he torched a fleet of invading Roman ships by harnessing the power of the sun. The story still attracts interest. In 2005 a team of American scientists from MIT tried, with limited success, to recreate Archimedes’ ‘death ray’ for the television programme Mythbusters.

The siege of Syracuse in 212 BC cost Archimedes his life. The story goes that he was drawing figures in the dust, oblivious to the events around him, when a Roman soldier demanded that he should accompany him. It’s said his last words before the angry soldier killed him were, ‘Don’t disturb my circles!’

For more Pharos links and images on my pinterest page click here.

![The Mirror of Pharos Archimedes Thoughtful, Domenico Fetti [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.jslandor.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Archimedes-Thoughtful-Domenico-Fetti-Public-domain-via-Wikimedia-Commons.jpg)

Buy The Mirror Of Pharos from the Author

Buy The Mirror Of Pharos from the Author