Why children’s writing?

When you write it sometimes feels as if the story is sent to you. You are the servant, the story is the master and you have to do what you’re told! So far I’ve only ever been sent stories for children.

My memories of my own childhood are very vivid so that has something to do with it. Drawing on them helps me reconnect to that time. And having lots to do with children is another factor. I managed a village pre-school for several years and wrote many stories and plays for my two sons.

Children are also wise. Their imaginations are like elastic, stretching and stretching without seeing the barriers that grown-up minds often build. So writing for children gives me the freedom to spread my wings.

Madeleine L’Engle, who wrote one of my favourite books, A Wrinkle in Time, said: ‘You have to write the book that wants to be written. And if the book will be too difficult for grown-ups, then you write it for children.’ Her book was famously rejected by 26 publishers. Now it’s a classic and a film is due to be released next year. It made a big impact on me.

Can you describe where you work?

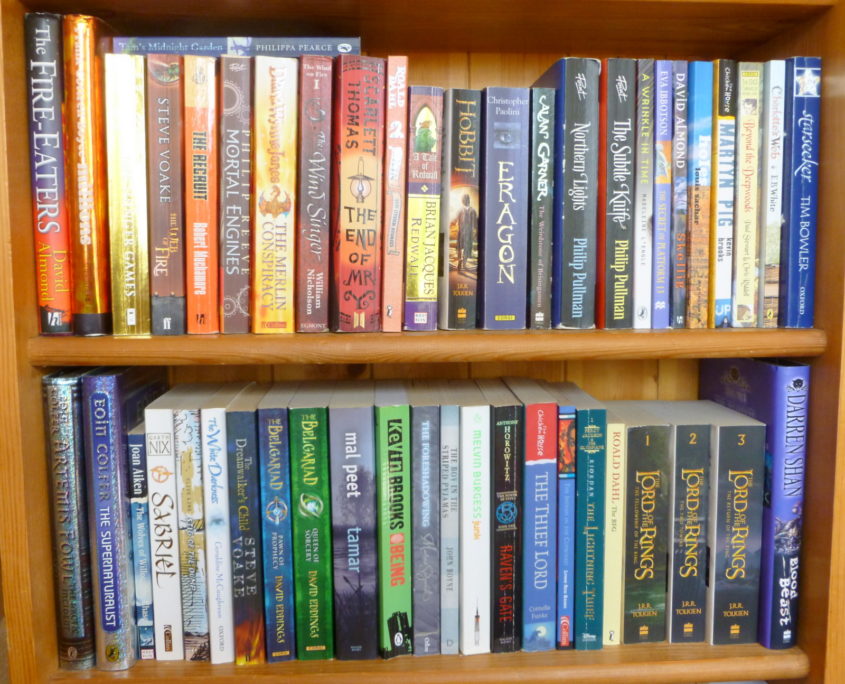

I write in the smallest room in the house. Yes, my study is tinier than the bathroom! But I love it because it’s a cosy den with bookshelves up to the ceiling and a big window. I’m surrounded by fields so I can look out and see deer, pheasants and hares passing by.

Buster is usually on the desk beside me. He’s my black and white cat and the inspiration for Odin, one of the characters in The Mirror of Pharos. You can read about him here.

When I get stuck or if the right words won’t come, I either play the piano, or pick up a notebook and pencil and go to the treehouse. I like to do free flow writing up there, anything that comes into my head. It’s great when the wind is blowing, like being on safari.

When do you write?

Every day, if I can. I’m a night owl and often keep going until one or two in the morning. It’s such a calm and magical time when the rest of the world is slumbering. Sometimes I can hear real owls hooting.

Even when I go to sleep I occasionally wake up with another idea. I keep a notepad by my bed so I can jot it all down. I think it’s true that when the conscious mind closes down the unconscious stays open and receptive.

Early mornings aren’t great for me, to put it mildly! I do household chores when I get up and need at least three cups of tea before I’m ready to sit down at the computer again.

What’s your favourite season?

The autumn. No question about that. Again, it’s a childhood thing. Apples, blackberries, pumpkins… Nature’s colourful grand finale always makes me feel elated. The shortening days tinged with melancholy, the smell of ploughed earth and the prospect of bonfires are definitely part of it. And I still can’t resist kicking up the leaves!

The Mirror of Pharos is set in the autumn with blustery winds that have a supernatural source. When I began writing, one of the first things I pictured – apart from a pair of amber eyes – was yellow and orange leaves falling like ticker tape.

What are your favourite books?

The honest answer is they keep changing, depending on what I’m reading. But I’ve always loved books that played with time and the concept of eternity.

Childhood favourites included Tom’s Midnight Garden by Philippa Pearce, A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle and When Marnie was There by Joan G Robinson. (I’ve discovered there’s a Japanese anime film based on the last one. It’s good. But I’d recommend reading the book first and imagining it your own way.) A beautiful one I read recently was Jessica’s Ghost by Andrew Norris and I loved The Foreshadowing by Marcus Sedgwick.

I also enjoy portal stories, the kind that begin in the real world, then take you by some clever device to another time, land or parallel universe. Philip Pullman does this brilliantly in The Subtle Knife, the second book of His Dark Materials. There are lots of others, of course. I’ve listed some more below.

Where do get your ideas from?

Ever since I was small I’ve made up random stories in my head based on things I notice. So if, for example, I saw a single glove on a park railing, I’d immediately think up a scenario for why it was there. Then I’d try to imagine the life of the person who might still be looking for it.

I think everyone has ideas like this. It’s daydreaming really. The trick is to notice that you’re doing it, then have fun developing the idea. You do that by asking lots of questions. What if this happened? Or that? What if the glove owner hadn’t actually mislaid it? What if someone left it there deliberately? Could the glove be a signal? Actually, why is one finger pointing at that manhole cover in the road? Who or what is down there? Eek.

Your imagination is like any other muscle; if you keep flexing and using it, ideas and stories arrive.

You can read about the inspiration for The Mirror of Pharos here.

Portals and where to find them

- wardrobe – The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe, C S Lewis

- magical flight – Peter Pan, J M Barrie

- ruined church – Elidor, Alan Garner

- platform 9 ¾ – Harry Potter, J K Rowling

- tornado – The Wizard of Oz, L Frank Baum

- mirror – Reckless, Cornelia Funke

- rabbit hole – Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll

- board game – Jumanjii, Chris Vann Allsburg

- tollbooth – The Phantom Tollbooth, Norton Juster

- magic rings – The Magician’s Nephew, C S Lewis

- door in a flat – Coraline, Neil Gaiman

Buy The Mirror Of Pharos from the Author

Buy The Mirror Of Pharos from the Author